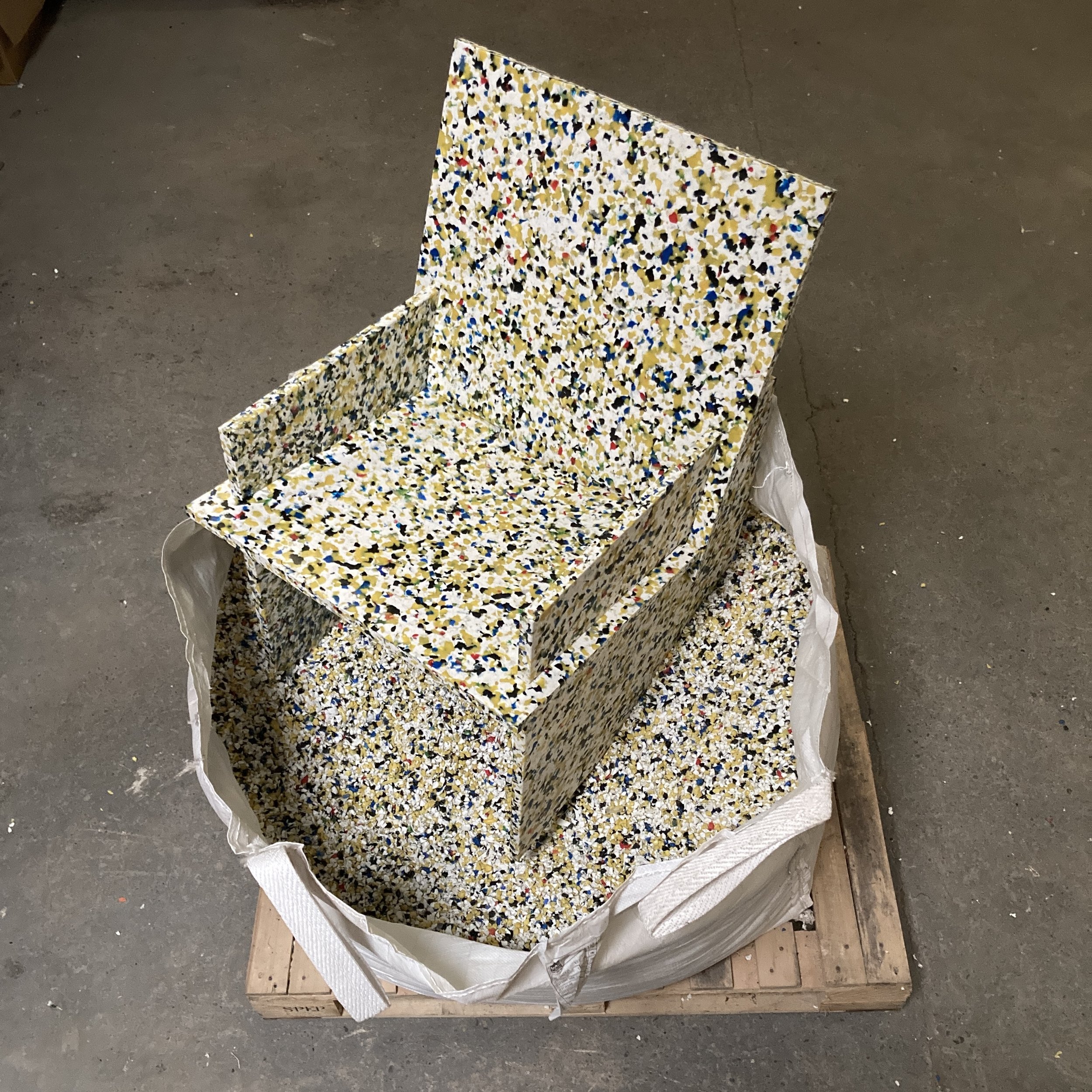

Our conversion of a former cow shed into a canine wellness centre for The Paw Project is complete.

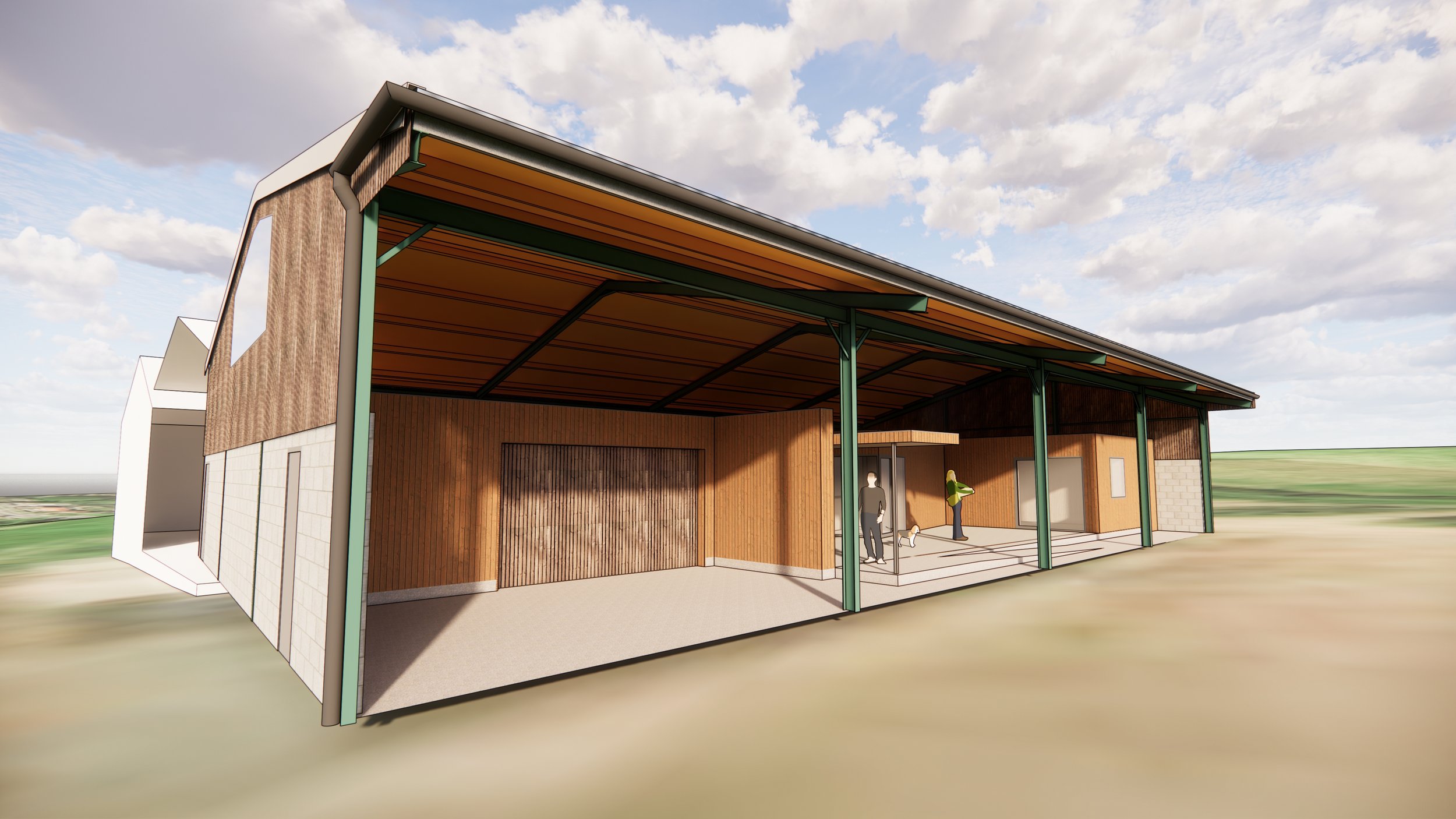

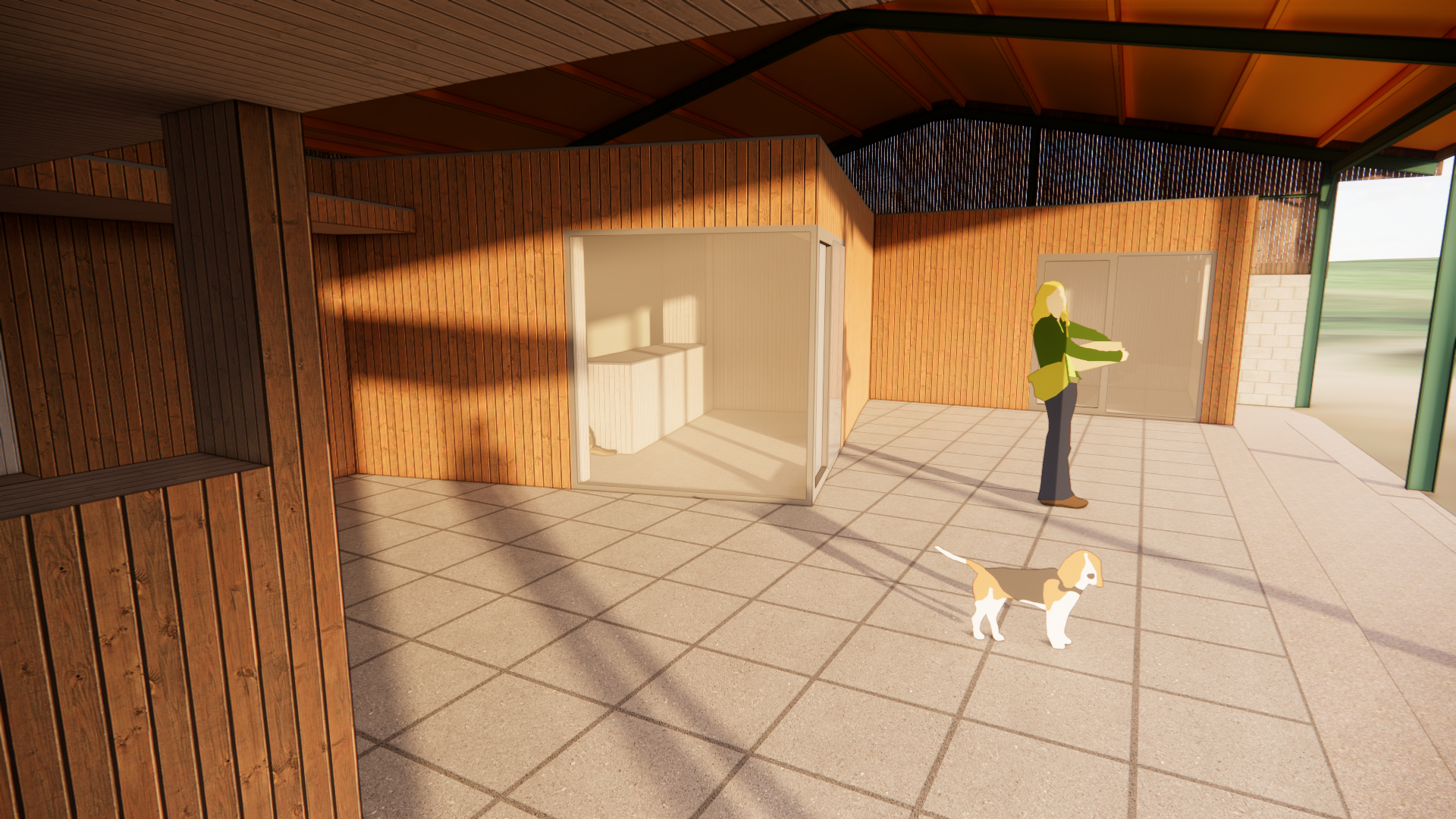

We opted to keep the new development low and spreading to create a welcoming outdoor sheltered space for owners and their dogs. This lack of formality reduces stress for the dogs, giving them space to mingle and to see where they are going.

Two main enclosed spaces house an office and acupuncture studio, and a grooming and treatment area. An open barn-like space is hidden behind a sliding gate for use for agility and behavioural classes.

A seating area and sales point/event space are located under a protective canopy, creating an intimate scale under the soaring barn roof. These features, along with the enclosed spaces, screen the rear of the barn from view.

A phased development plan means that there is space to expand the facilities in the future, whilst presenting a complete environment to visitors in the short term.

Client: @the_pawproject Design & build contractor: Sheltered Spaces