Our collaboration with the artist

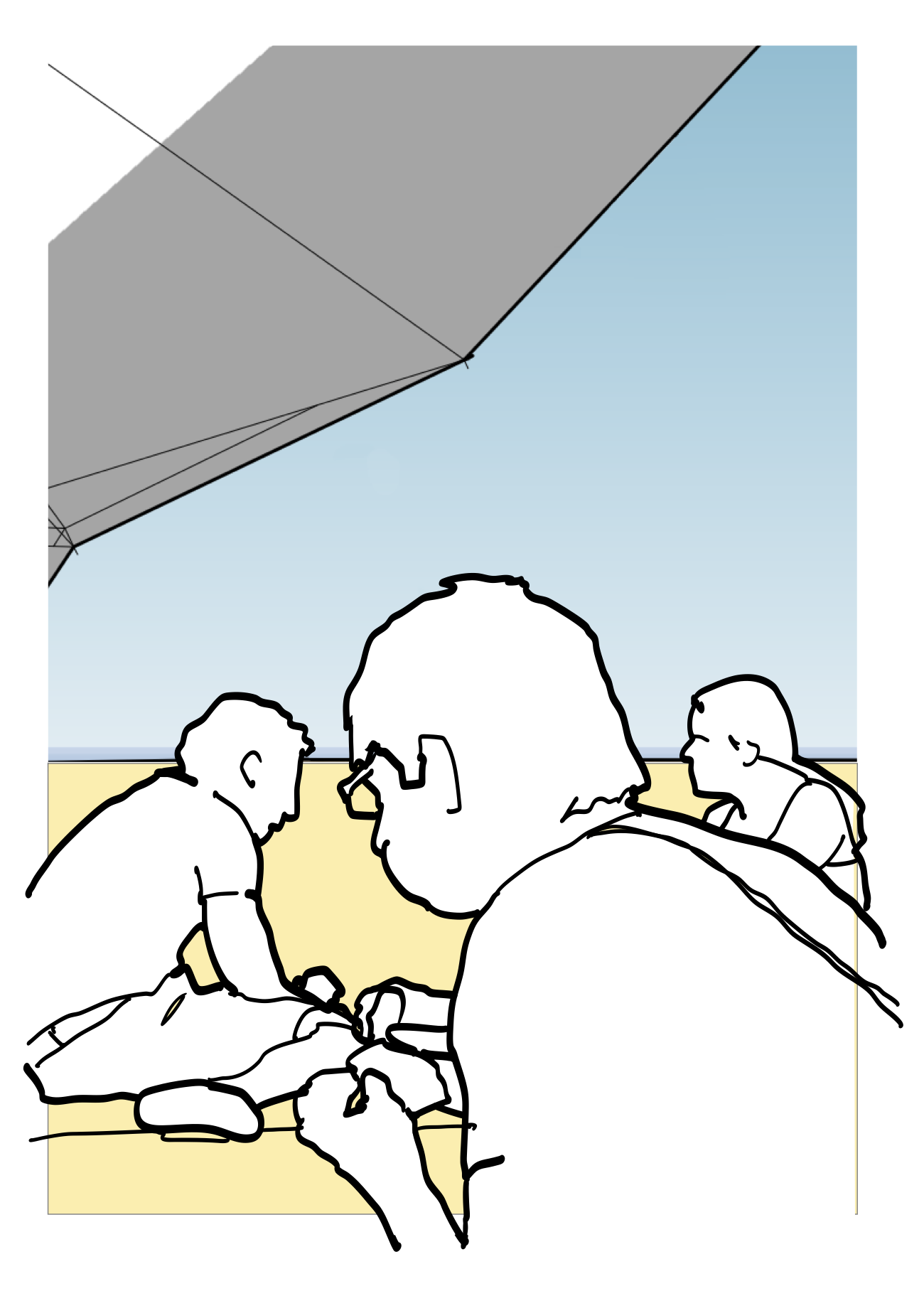

We found that Tristan shared our approach to understanding the project and our chosen site at Wolla Bank. We took our cameras and tape recorders and had a picnic in the dunes. We talked and sketched and thought, but we also interviewed everyone we could — hikers, families, fishermen, dog walkers, bird watchers.

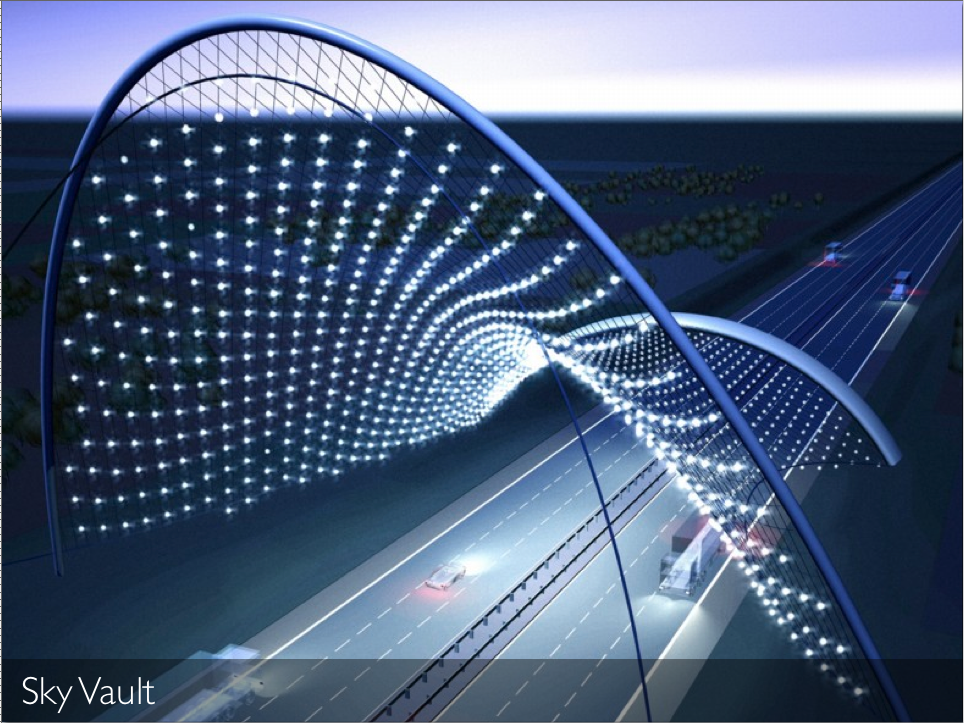

It became obvious that it was the remoteness and rawness that they appreciated. All of them had visited Wolla Bank many times, and they all praised its quietness and undeveloped nature. Rather than change the place by inserting an icon that would signal development, we decided we should intervene in a strong but subtle way in the landscape.

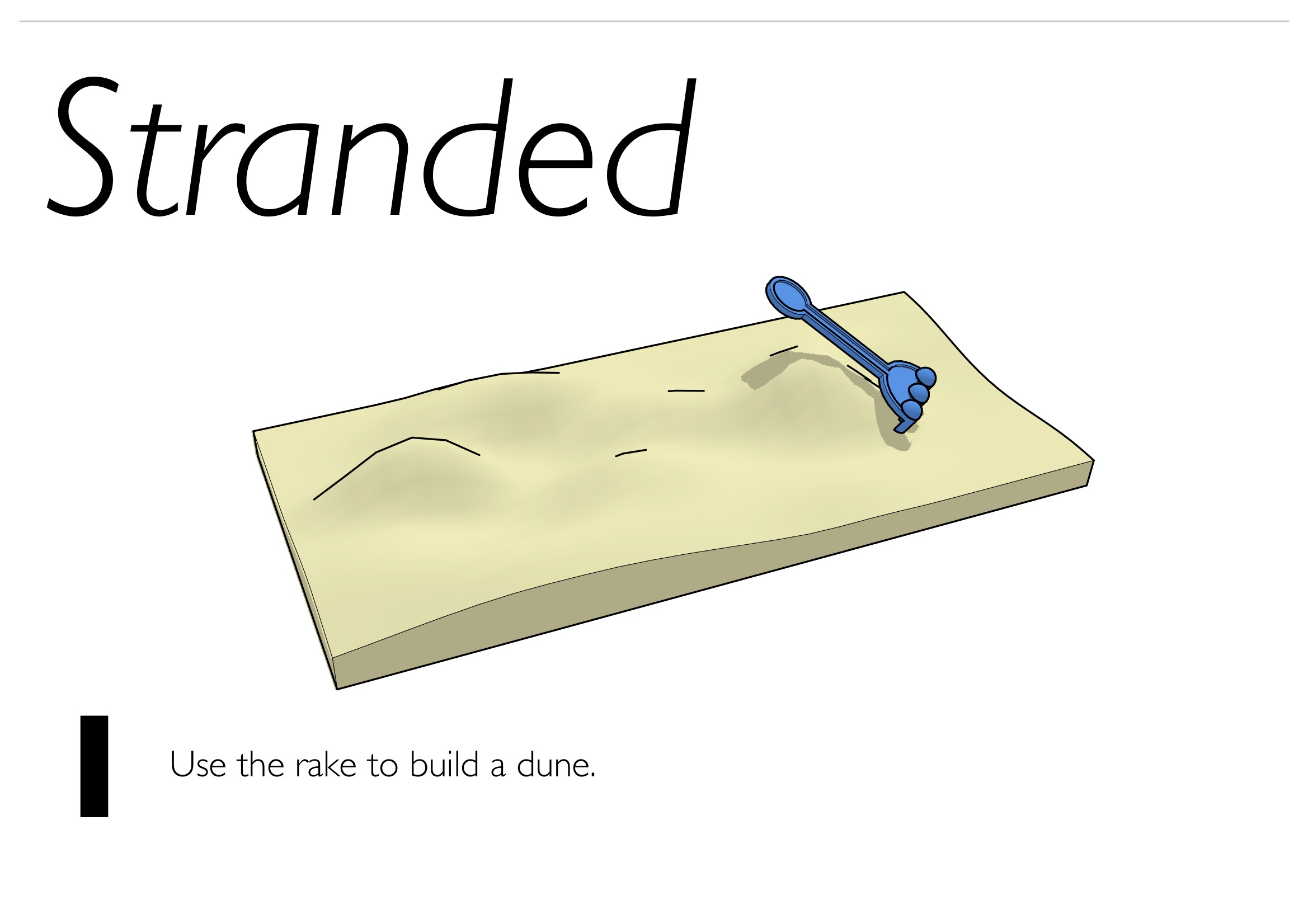

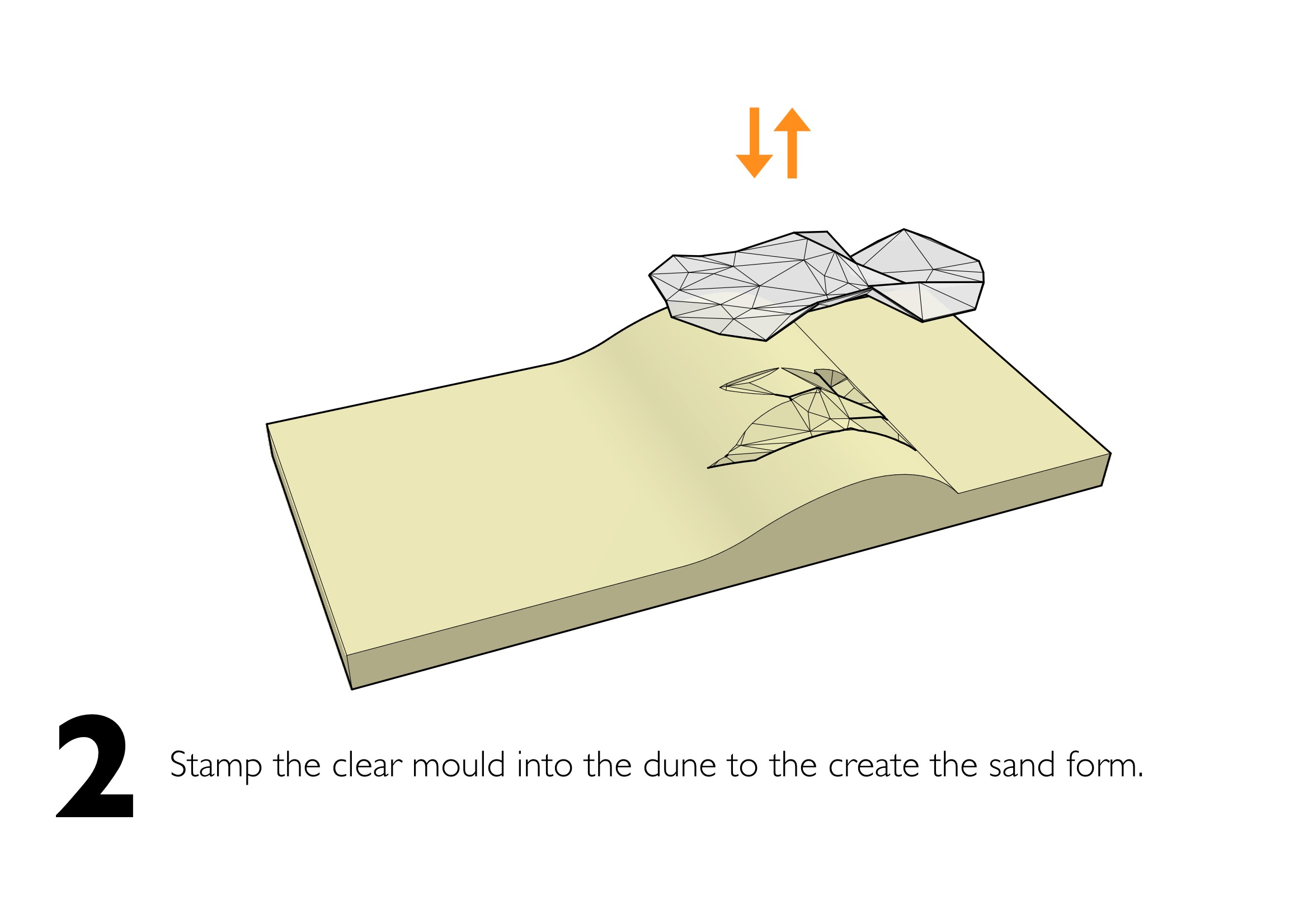

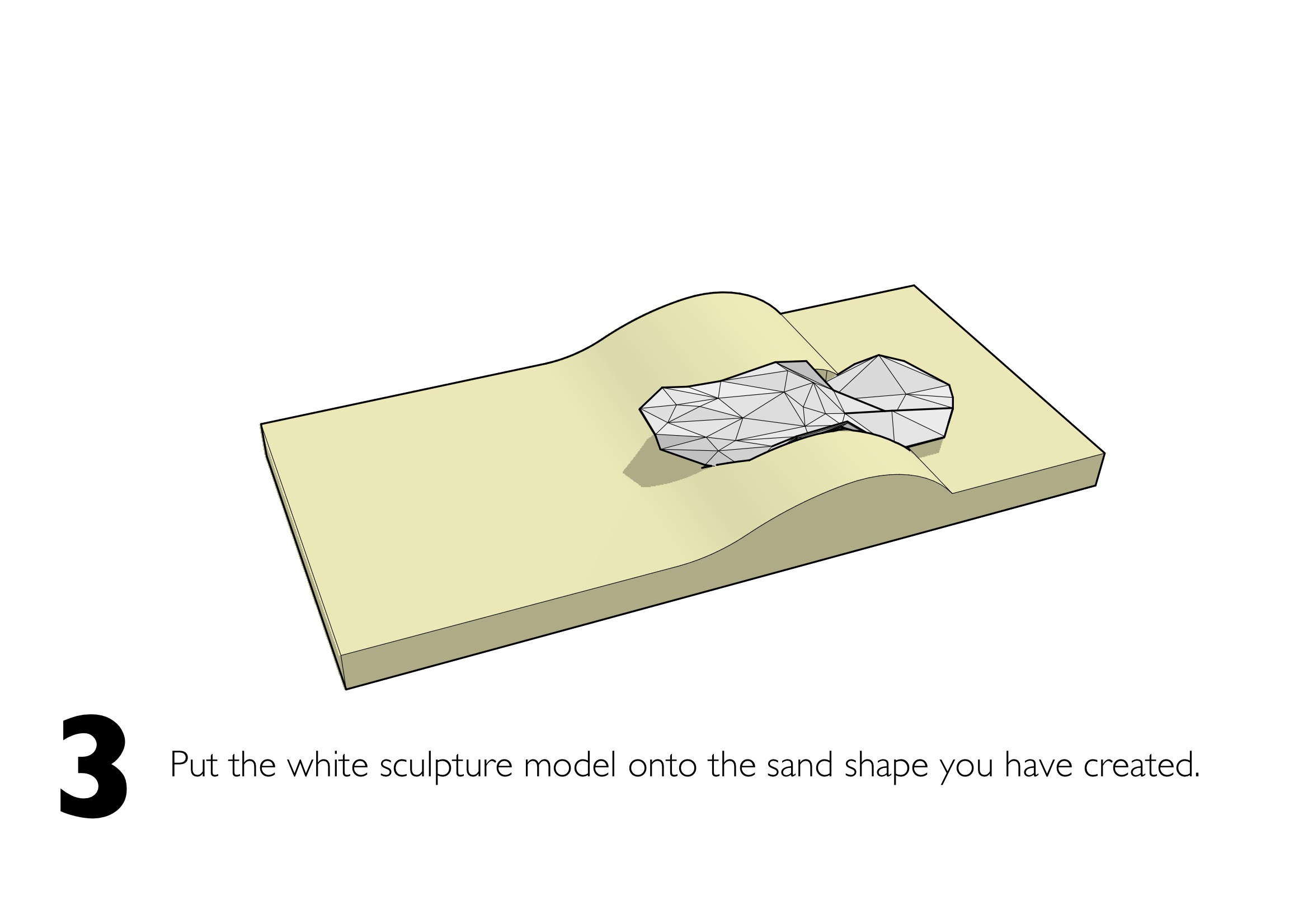

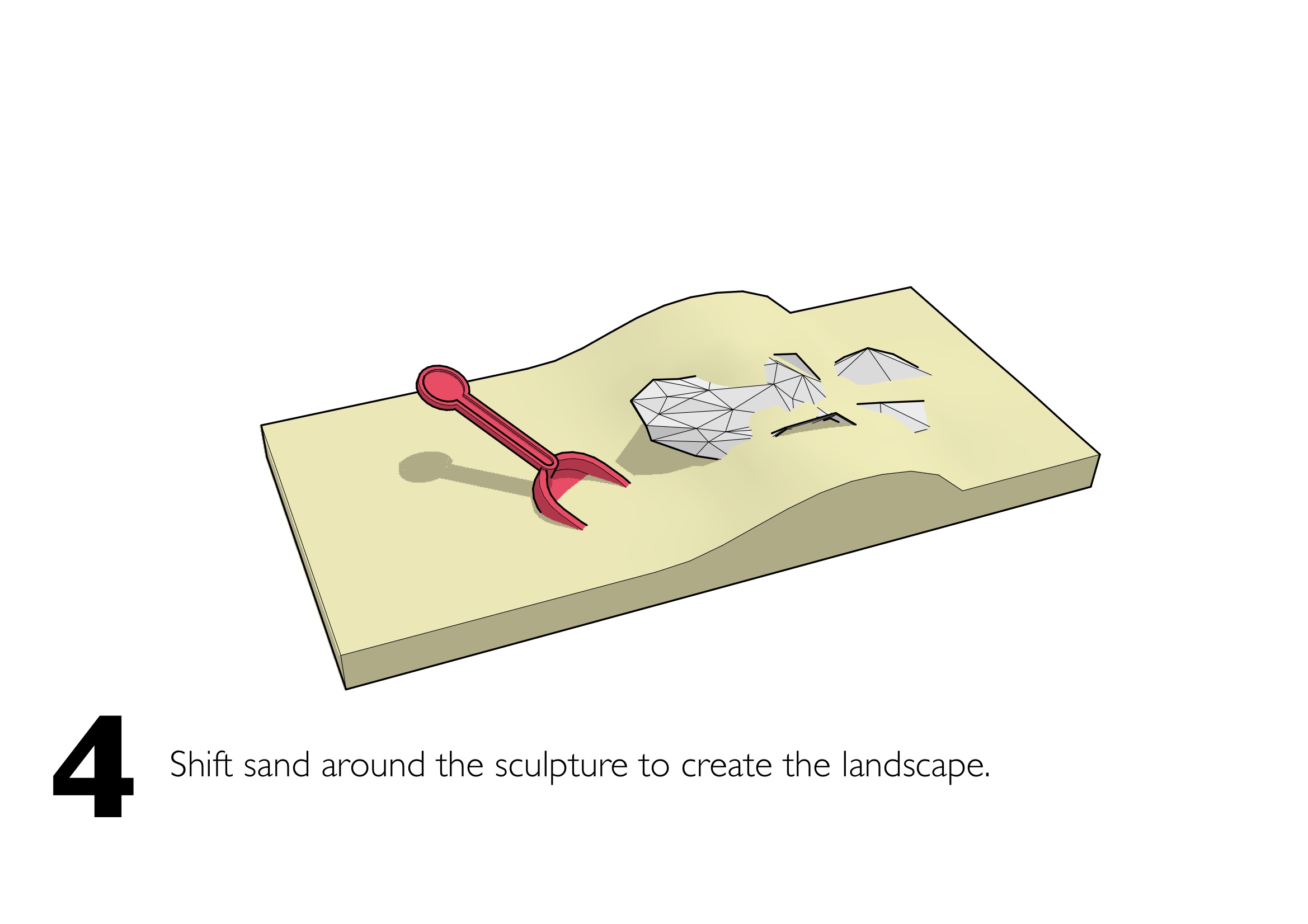

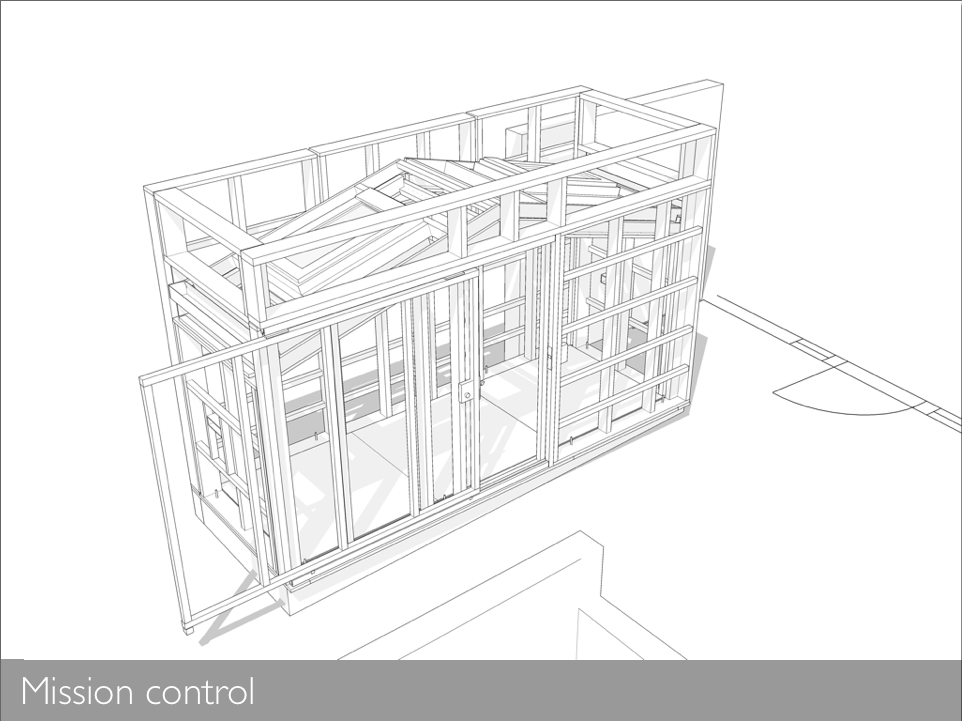

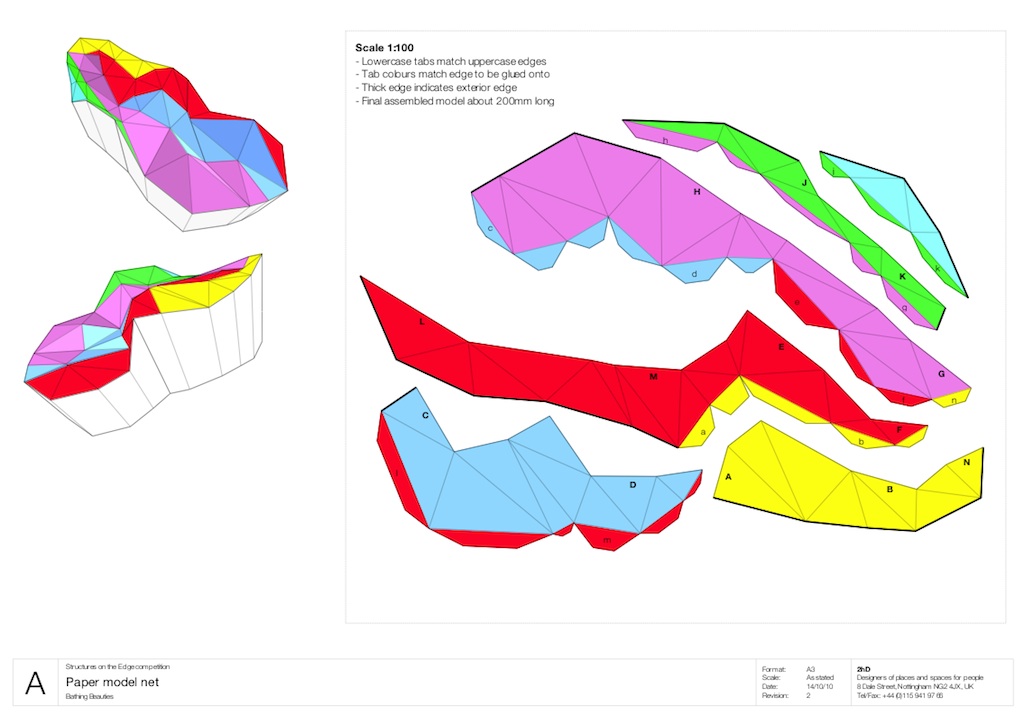

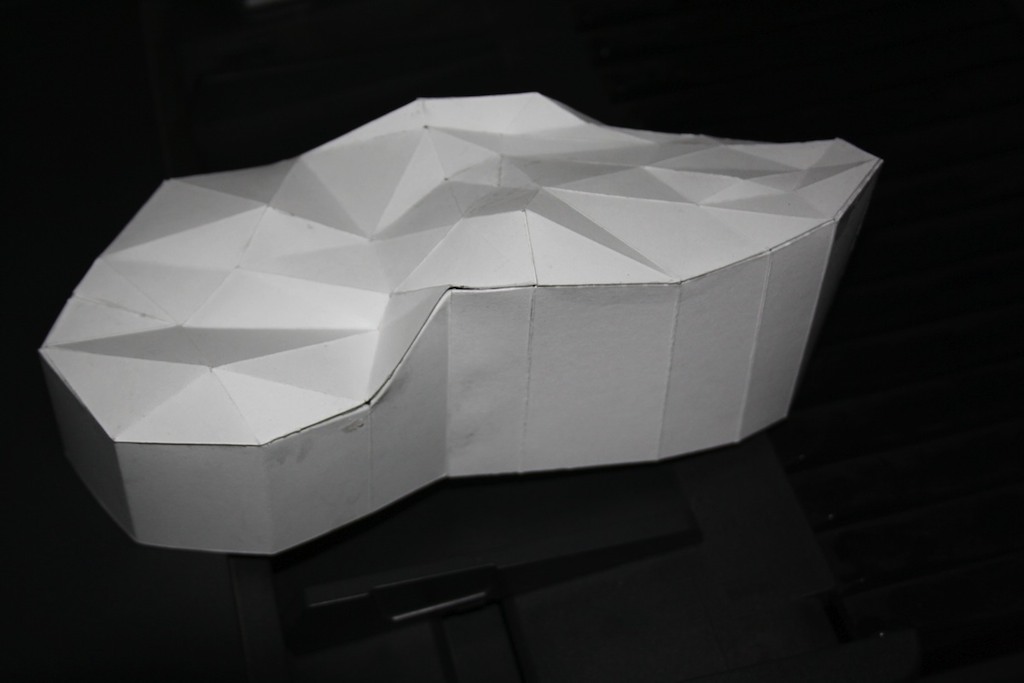

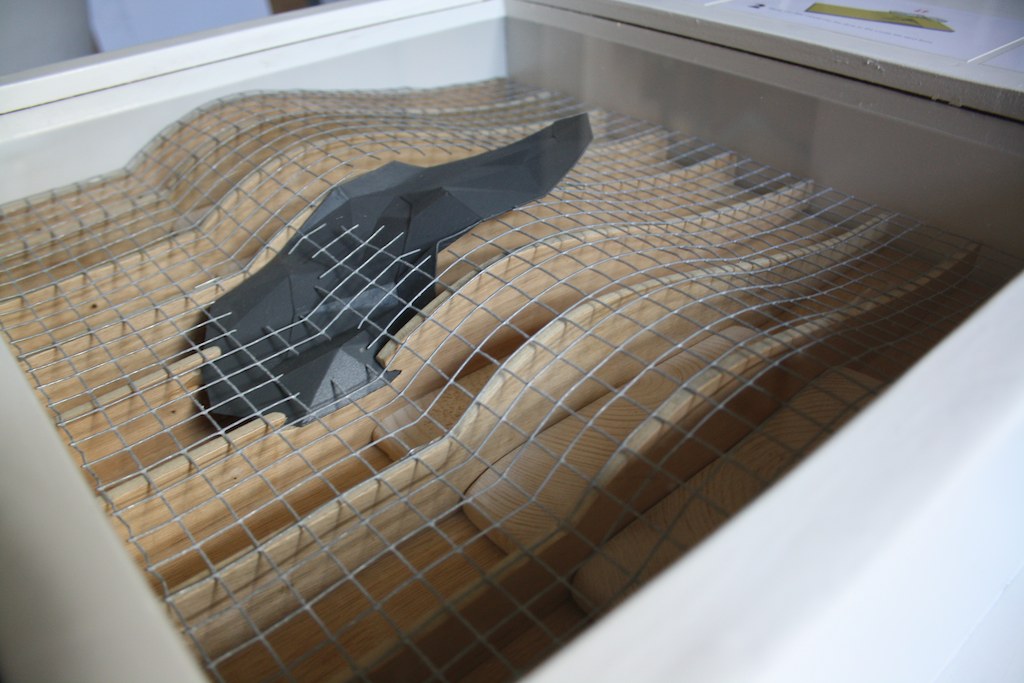

The making

The process of making Stranded would be intimately connected to these intentions. Creating a mould from the sand of the dune, we would dig out areas of the structure which would be ultimately submerged beneath the ground, and build up areas that would be raised. Finally, we would spray on fibre reinforced concrete to form the structure. The process would be like building a giant sand castle — a hands-on process through which we would engage the local community and visitors.

The exposed concrete areas would collect sand and be blown clean so that the structure would change over time, a process that we would document and that would help to explain the life, mobility and sensitivity of dunes to the visitor.